Varlam Shalamov, “Kolyma Stories” (1972) (translated from the Russian by Donald Rayfield) – Conservative moralists squat on top of the literary memorialization of the Nazi death camps and the Soviet gulag, even though the pair I have in mind, Elie Wiesel and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn respectively, are both dead. Both are well worth reading but both also seek to isolate their particular instances of evil from history and politics, insisting on their metaphysical uniqueness and priority. This impulse has, ironically, loaned these historical memories to political projects of many blunt, history-distorting, and violent kinds, starting with the totalitarianism school and ranging from Zionism to post-Communist revanchism in Eastern Europe to whatever nonsense Jordan Peterson was selling before he took his current protracted disco-nap.

Wiesel and Solzhenitsyn got the Nobels and, more importantly, sit the perch where one is taught to generations of western high schoolers and undergrads as the definers of totalitarianism. Other voices were always out there and some, like Primo Levi, even had pretty good traction, though no Nobels, for those playing the home game. Gulag memoirist Varlam Shalamov has been published now in English both by Penguin and in those snazzy NYRB Press editions, but to the best of my knowledge hasn’t penetrated the western public that much.

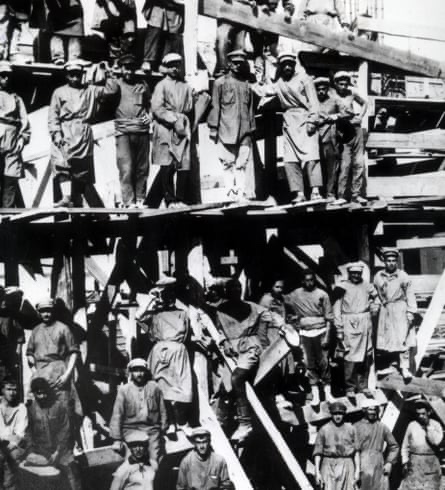

That’s a shame, as he’s a great storyteller. He was a Trotskyite, sent to the Kolyma mining colonies in the far northeast of Russia during the great purges of the 1930s, and stayed out there for seventeen years, until things started cooling off after Stalin’s death. Shalamov credits his longevity to having made it, after a few deathly years in the mines, into a paramedic program, and the stories he began writing after his release have a sort of medical acuity to them, an eye for symptoms and diseases, pain and humor. He gives a depiction of life stripped down its most brutal basics: the hunt for food, warmth, and security in an environment lacking all three. At bottom, he reiterates in several places, the camps strip the humanity from their inmates (and staff, in a different way), leaving only anger out of all the sentiments. His fellow Trotskyites came in already dehumanized from the tortures they experienced before being sent away; others, like the prisoners of war who had the bad luck of escaping from German captivity only to be sent to the Gulag, fought back more. But mostly, these are stories of work, food, theft, negotiation over the stuff of life.

One obvious difference here with the Solzhenitsyn school of memorializing the Gulag is that Shalamov doesn’t moralize, or moralizes differently. For one thing, he went in a communist and as best I can tell, came out one, just of a shade disapproved of by Moscow. Shalamov harps on two things, and you can tell they were the preoccupations of someone who was still thinking like a camp prisoner: first, don’t romanticize criminals, as Russian (and other) intellectuals are wont to do. The gangsters in the camp made everything worse, an additional transaction tax of shit added to the already shitty situation they were in. Second, nothing about the experience of forced labor was ennobling, as the Soviets insisted on during (and after?) the high point of the Gulag system, and going through it didn’t grant any metaphysical insight. You can see why this appeals to western audiences looking for Cold War or post-Cold War morals less than other writers of the totalitarianism experience, but it also reads true. *****