When I was maybe twelve or so, my dad got in maybe his last real zinger on me, and what’s more, I’m pretty sure he didn’t mean to. After seeing a certain display at a Waldenbooks, I asked my dad if he knew anything about “alternate history.” He looked at me, a little puzzled, and asked “you mean, like Howard Zinn?”

No, listener, I did not mean Howard Zinn. I had nothing in mind that pointed to me being a good virtuous little leftie or particularly interested in learning anything useful. When I said “alternate history,” I meant novels set in worlds generated by asking historical “what if” questions. I’m not going to dwell too much on definitional questions — arguably, every novel set on Earth in the past or present is an alternate history novel given they all posit something happening that did not actually happen, yadda yadda — and simply say that for the purposes of this lecture, I define “alternate history fiction” as fiction where a historical counterfactual is a major part of what sells the book to audiences- the usual punt to the power of marketing to define literary categories that critics under late capitalism so often make, but there it is. And it was marketing that drove me to ask my dad about alternate history that day, namely, a display of alternate history novels by writers like Harry Turtledove, S.M. Stirling, Steven Barnes, and other stalwarts of the subgenre.

Alternate history fiction in the form we know today came about when the form jumped the track, from a plaything for historians — from Titus Livy to Winston Churchill — into the emerging genre of science fiction. This was in large part due to various conceits that became common in alternate history stories and that are still present today: time travel, dimension-shifting, various divergences in the history of science leading to technological leaps, on and on. But the identification of alternate history and scifi was so complete by the time I was paying attention in the late nineties that alternate history stories without such conceits, where there’s no time travel or magic or advanced technology, were still usually considered scifi and shelved as such at bookstores and libraries… unless they were written by established literary figures, such as Philip Roth or Michael Chabon, both of whom wrote alternate history novels that are generally considered literary fiction, albeit with some genre flavor.

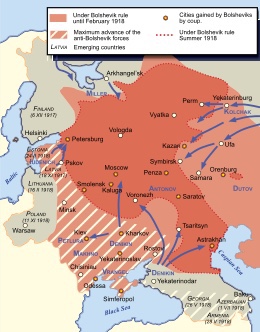

Widely-admired works of alternate history fiction, including L. Sprague DeCamp’s Lest Darkness Fall, Ward Moore’s Bring the Jubilee, and Philip K. Dick’s The Man in the High Castle dot the scifi landscape throughout the twentieth century. But something changed in the late nineteen eighties, and this change gathered strength in the nineties and early aughts. Alternate history became a mainstay of science fiction. Many authors dabbled in it but a few became dedicated writers of alternate history science fiction, writing little else, and often cranking out multiple such novels a year. Literary fiction got in on the act, too, as with the aforementioned works by Roth and Chabon. So did TV, in the form of the show Sliders, which began as a show about a group of people forced to travel to a series of alternate dimensions with different histories (that eventually became a monster-of-the-week show). No less a figure than Academy Award winning actor Richard Dreyfuss co-wrote a novel about an America where the American Revolution didn’t happen with Harry Turtledove published in 1995 (they were going to make a movie but it didn’t get anywhere). Newt Gingrich slapped his name on some co-written alternate history novels between 1995 and 2011. Hack historian Niall Ferguson put out a book of “Virtual Histories” in 1997, a cheap cash-in that tried and failed to take shots at leftist history, mostly on the basis of great social historian E.P. Thompson having called counterfactuals “ahistorical shit.” There was a flourish of alternate history discussion groups online, on usenet, on webrings, and so on.

This moment in the sun for alternate history fiction coincides with two relevant stretches of time. One is my childhood, as well as the portion of that childhood spent reading a lot of alternate history fiction- roughly ages twelve to eighteen, when I gobbled down works by Harry Turtledove, S.M. Stirling, Eric Flint and others. I bothered my friends talking about them (though my friends Miri and Phoebe were sweet enough to take me to see Harry Turtledove speak at a local scifi convention), attempted to write stories in the genre myself, and made one of my best friends in college when we gingerly admitted, with the shame that nineteen can have for seventeen, our respective alternate history reading phases to each other.

The alternate history moment also coincides with the era we now sometimes, ironically, call “the end of history.” This is named after one of the great whoppers of bad historical prediction, one so bad you have to figure someone could write a decent alternate history story based on the idea of “what if Fukuyama was right?” Francis Fukuyama was a neoconservative intellectual who wrote the essay “The End of History?” in 1989, where he suggested that with the impending collapse of the Soviet Union and with it the dream of communism, history — capital H History, in the Hegelian sense, as in conflict over what ideology should guide politics and society — was over, and that liberal democracy, American style, had won the day. This was turned into a book in 1992, and became that rara avis, the Hegelian bestseller.

You could call the “end of History” era the period where serious people could buy what Fukuyama was selling. Ironically, Fukuyama himself, one of the more thoughtful of the neocons, was less bullish for the concept than many others. But for plenty of “thought leaders” at the time, the world was destined to look more and more like America in the nineties as time went on.

When did this era end? Some would say 2001, with the 9/11 attacks. While I see the point, I think in many ways the reaction to 9/11 was guided by the sort of people who believed in the “end of history” thesis and that Islamic fundamentalists were just backwash to be mopped up, many of these people being Fukuyama’s fellow neocons. 2008, with the financial crash and the resurgence of white revanchism that reared its head with Obama’s election is my general stopping point for the end of history.

The late eighties was also when figures like Harry Turtledove and S.M. Stirling began writing alternate history stories. Arguably the best alternate history novel of that period, Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain, came out in 1988. On the other end of the End of History, the break is less clean, but Harry Turtledove concluded his 11-book series that begins with the Confederacy winning the US Civil War with one last novel in 2008. The major figures of nineties alternate history continue to publish in the subfield, and new writers take up the concept as well, but I think things shifted, somewhat, as the twenty-first century wore on.

I guess now is as good a time as any for a thesis, isn’t it? I put it to you that the high point of genre prominence for alternate history occurred when it did due to a concatenation of circumstances that we can see as characteristic of the “End of History” era. This is not simply a matter of cultural or ideological critique, though that enters into it as well, but is also a question of material conditions pertaining to the production and consumption of popular art. As these conditions shifted in the post-2008 period, so, too, did the place of alternate history fiction.

A caveat, here, around the question of “high points.” I would not say that the alternate history fiction produced during the “end of history” era is the best alternate history fiction out there. The products of the subgenre from that era range in quality from quite good, like Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain, to absolute drek, like Niall Ferguson’s work and much of Sliders. In general, I’d say they tend to the formulaic and the lower end of mediocre. This was, above all, the era of series, as exemplified by the work of Harry Turtledove, who at various points in the twenty years we can call the “end of history” worked on no fewer than eight series that could be called alternate history, all of them at least three books long, alongside multiple standalone alternate history novels. Other major alternate history writers followed suit, and some of these series, like Eric Flint’s “Ring of Fire” which he began in 2000, are still being written. These series tended to have concepts that did most of the work for them, with action, worldbuilding, and characterization varying in quality but generally being a little pro forma. Whatever their quality, these blockbuster series, many of them bestsellers that hooked a lot of readers, helped fill out the sorts of chain bookstore displays that first notified me of the genre. This would have been difficult to do with, say, alternate history fiction in the early nineteen-sixties, when works like The Man in the High Castle, miles better than any Turtledove pot-boiler, came out, but weren’t understood as representing a discreet subgenre for marketing purposes.

I argue that things changed in alternate history fiction after 2008 or so. But of course, most stories of historical rupture carry with them elements of a story of history continuity (and vice-versa). There is continuity in the story of alternate history fiction across the 2008 barrier, but there’s rupture too. Let’s see if we can’t parlay continuity into rupture in both the alternate history sphere and the larger historical context. One continuity between our post-2008 period and the “end of history” era in which so many of us were born and raised has been the steady progress of a few economic trends: rising wealth and income inequality, stagnating wages and increasingly precarious job security, the delinking of productivity gains from wage growth and increases in standard of living, the consolidation of wealth in fewer and fewer hands and of corporate power in an ever-smaller number of conglomerates.

This sadly familiar tale has a bearing on our story in a few ways and continuity and rupture across the 2008 line do-si-do with each other in both the realms of alternate history fiction and of the broader political and cultural context. The speculative fiction industry, like the culture industry more broadly, has seen a bifurcation- big name writers make big money, usually with big tentpole series that compete to become movies and tv shows, while millions of other, less fortunate scribblers find other outlets for their work than conventional publishing, especially self-publishing (now enabled by Amazon to sell directly to consumers) and fan fiction.

This dynamic was somewhat less pronounced at the beginning of the “end of history” era in the late eighties than it is today. You could argue that a lot of the alternate history writers of the time existed in a sort of broad middle class of speculative fiction writers, the sorts of people who read and wrote for the pulps back when they were still relevant and cut their teeth on the expanding paperback market of the mid to late twentieth century. But we all know what happens to middle classes when the top decides to rake back their wealth and power, and there’s no meaningful opposition to stop them. Arguably, the creators of big alternate history series in the End of History era — Harry Turtledove, S.M. Stirling, Eric Flint — made it past the big thresher, into the lower strata of the series-producing scifi gentry, though they’re small-fry compared to your J.K. Rowlings and George R.R. Martins.

Inequality and a general feeling of stagnation or decline also spurs discontent. This is true in the literary realm as it is in the political realm, though if the linkage between discontent and action can get blurry in the political world, it gets downright warped in the world of culture. In an altogether too neat analog of so many political situations the world over since 2008, the speculative fiction community, in the anglosphere in any event, has grown its very own red-blue divide. It maps neatly onto the red-blue divide in mainstream American politics (and which spreads like a weird memetic virus to other political contexts the world over), complete with a febrile, fascist-adjacent red team and a smug, complacent blue team, and masses of people and many pressing questions left out of the equation.

This manifested itself most dramatically in the “Puppygate” saga, where various coalitions of right-leaning scifi and fantasy writers ranging from libertarian contrarian cranks to out and out Nazis tried to hijack the Hugo Awards nomination process, one of the big award ceremonies in the speculative fiction community, or else burn the award’s credibility to the ground. The different “Puppy” factions (you see, they’re ironic, which means they can’t actually be terrible pieces of shit, etc etc) did this out of spite for what they saw as a liberal elite of writers and editors imposing social message fiction on a mass of readers who just wanted spaceships and lasers.

Unlike certain other encounters in the 2013-2017 period in which the Puppygate fiasco happened, the blue team decisively won. N.K. Jemisin, author of the Broken Earth novels and target of much abuse from the Puppies as a “social justice warrior” and a black woman, won three Hugos for best novel in a row. For now, it seems that the red and blue camps in contemporary scifi are here to stay for the foreseeable future, sniping at each other online and conforming more and more to type — the conservative gobbler-up of identikit military scifi stories of buff guys in power armor shooting aliens, the liberal mark for any story pitch with an oppressed narrator and a few buzzwords — as mutually antagonistic believer communities so often do.

It’s not strictly symmetrical. The “red” side, led by the Puppy factions, really did harass and try to disrupt the other side in ways the Blues didn’t do back to them. If you want your scifi to jump the track to mainstream respectability, it helps to have the literary ambitions, social relevance, and better editing (and less cringeworthy cover art) of “blue” favorites like Jemisin, Ann Leckie, and so on… though that doesn’t always translate to superior sales numbers, as any number of pulpy populist stalwarts like Jim Butcher or David Weber can attest to.

Alternate history fiction enters into this dynamic mostly on the margins. One of the bigger social-media brawlers in the notoriously rough playground that is young adult fiction, Justina Ireland, started a YA alternate history scifi series about slavery and zombies, and she doesn’t hesitate to wade into speculative fiction fights on the blue side (her day job is as a defense logistics professional for a US Navy contractor, as it happens). But most of the big players in high-stakes speculative fiction drama aren’t mainly known as alternate history writers. As I will discuss later in this lecture, I don’t think it’s accurate to say that alternate history has gone into eclipse since the End of History period, but it’s place in the genre and the culture at large has changed.

This is where the long suffering listener might be thinking that we’re finally going to get into the ideology critique- how alternate history fiction has changed with the changes in prevailing ideology between the late eighties and today. Of course you all know I’m a materialist so I throw in stuff about material conditions, but we’ve read enough leftbook-shared articles to know that now’s the time when I lay the ideology bare. Well, far be it from me to disappoint my guests, but I’m gonna play with it a little. I think changes in ideological bent — the values expressed that map, more or less neatly, onto contemporary set-piece political battles — are only one strand in a braid of ruptures and continuities that run not just between contemporary alternate history fiction and that of yesteryear, but between any set of coordinates in cultural past and present. In short, I’ll give you your ideological meat but also your historiographical veggies.

It won’t surprise anyone to learn that the main ideological differences between alternate history of its peak period in the nineties and aughts and alternate history today is found in treatment of race and gender. It would be pretty easy, and even true enough, to say that earlier alternate history had problematic takes on those subjects, and contemporary alternate history is more “woke.” Consider some of the plots of big time alternate history works from the nineties and aughts: Harry Turtledove’s “The Guns of the South,” where Afrikaner militants use a time machine to give General Lee’s armies AK-47’s, the same author’s Southern Victory series, depicting a victorious Confederacy sans time travel this time, Steven Barnes wrote a series about Africans enslaving white people to work in the Americas, and there’s my personal favorite, the Draka series by S.M. Stirling, where American loyalists fleeing the Revolution go to South Africa and create a slave superstate that eventually conquers the world. Then consider the premises of recent alternate history hits: downtrodden nineteenth century nations use magic and steampunk tech to turn the tables on the imperialists in P. Djèlí Clark’s work, the ANC and the apartheid South African secret police fight over an empathy machine, wandering circus folk disrupt a world run by Luddites, dinosaur riding Sioux do Dances with Wolves but with dinosaurs instead of horses with Colonel Custer’s son. A whole new world!

Maybe! But- there’s complications. Let’s look closer. I’ve seen people cite the basic premises of these books — especially the older alternate history novels I just cited — as prima facie evidence of the writers’ racism and reactionary sentiments (or lack thereof, in the case of more liberal-leaning recent volumes). I think it’s worth getting deeper in there and exploring what exactly these writers thought they were doing with race, gender, and politics more generally.

Let’s start with the material again: the big alternate history writers of the End of History era were all working scifi writers who made a living by cranking out a ton of writing, often multiple novels a year, usually in multiple subgenres of speculative fiction, and often had sidelines writing for tv or movies or for the tie-in novels attached to them; Terry Bisson, who wrote the excellent Fire on the Mountain, also wrote the novelizations of Johnny Mnemonic, The Fifth Element, and Galaxy Quest among others. Many of them have continued that work rate well into the second and third decades of the twenty-first century. What this means for us is that along with whatever points they are trying to make with their fiction, they primarily write to entertain. This doesn’t obviate the messages within their work, but it’s relevant to reading them that these writers needed to crank out a lot of prose, needed it to appeal to an audience, and needed ways to vary things up to keep the formulas fresh.

The model I developed when visiting or revisiting these works is less that any given writer had a line, a defined take on race or sexuality or power or whatever, but a space, a range of ideas they considered sufficiently credible or interesting or just relevant to put into their fiction. So the same guy, S.M. Stirling, who wrote about the white South African slave superstate also wrote a series about a black lesbian sea commander who uses her samurai swords to fights slavers (after nineties Nantucket gets zapped to the Bronze Age… it’s complicated). The guy who wrote the “Africans enslaving Europeans” series was black himself and wrote about different kinds of slavery and their relative merits, etc. Harry Turtledove wrote of a kindly Lee using his AK-47s to create a gently progressive Confederacy in The Guns of the South, but ended his Southern Victory series by lazily mapping the story of Nazi Germany onto that of the Confederacy, with black people filling in for the Jews. Let’s put it this way: in the mainstream of End of History era alternate history fiction, you will find no careers that argue, straightforwardly and schematically, the way we like it to be on the Internet, for white supremacy, slavery, misogyny, fascism, etc.

So what, then, is the space of thought in alternate history? What’s there and what’s not? Well, let’s get the obvious, for this crowd, out of the way first: communism is right out. Communism means Stalin, as far as Turtledove and Stirling are concerned, and moreover means weak competitors with liberal democracy and a lame villain next to fascism. No one but fanatical idiots believe in it in their stories, and they’re outnumbered by devious secret policemen and ideologues playing the system. The Draka, the South African master race Stirling devised, practice a weird sort of slave-driven corporatism, and it’s clear Stirling can more easily imagine that than an end to capitalism, and that seems to be the main line for alternate history at the time. There’s exceptions- Terry Bisson’s cooperativist New Afrika, founded by John Brown’s breaking of slave power in Fire on the Mountain, but that was exactly the kind of work your old scifi heads nod approvingly at and never reproduce. Eric Flint, author of the 1632 and 1812 series, was a Trotskyite, but is also clearly one of those dudes who working classed himself into thinking that working class revolution is bullshit because the guys in pickup trucks don’t talk about it. His good societies are vaguely social-democratic, but revolution to him is getting rid of inquisitors in seventeenth century Germany (a good first step, I grant) and teaming up with the most progressive king around (Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden and— no shit— Oliver Cromwell). It’s less that these writers were anticommunist and more that their visions were orthogonal to seeing any kind of communist or revolutionary horizon.

The radical left option is out of the box in End of History scifi. The radical right option is not. Genocide, slavery, and the redemption of various right-wing monsters loom all throughout End of History alternate history. The redemptive angle is especially worth considering, and here, aspects of vernacular historical thought inherited both from the culture at large and from speculative fiction tradition mesh with timely ideas and concerns to dress up old themes in new clothes. Harry Turtledove premises all of his work involving the Confederacy on acceptance of many tropes of Lost Cause historiography- Robert E. Lee as a kindly man who didn’t like slavery, the importance of states rights over and above the slavery question, the idea that the Confederacy could ever have been a normal, functioning country, let alone a superpower. The Germans eventually join Team Earth to fight off aliens when they invade during WWII in another of Turtledove’s endless series, because, as everyone knows, the German army was essentially smart and honorable, unlike that nasty Hitler fellow. The good dictator, the ambivalent slaver, the reluctant mass killer, made to be what they are by circumstances and their realistic acceptance of same, their humanity wrung for pathos on the rack of their (fun to read) misdeeds… we see these in a lot of science fiction and fantasy going back to the genre’s origins, and the old alternate history guys were thoroughgoing readers of the old school scifi and fantasy, we know.

Muddles, ironies, paradoxes, and the self-congratulatory consideration that wisdom is made up out of muddles, ironies, and paradoxes, constitute many of the coordinate points defining the space of alternate history fiction at the End of History. To the extent there is a hook to these books other than curiosity about the what-if premise and whatever action they boast, it is precisely the “made you think!” moment you’re supposed to have when you consider that perhaps the AK-wielding Confederate or the novel-writing slaver-soldier isn’t so different from you after all (another way in which Fire on the Mountain is exceptional- Bisson’s characters really are different along with the world, but still relatable). You can change the set dressing, move borders around on the big risk board, occasionally have more or less political freedom, but the basic structures — capitalism, our concepts of race, sex, gender, and so on, something like the nation state — do their structuring thing, providing scaffolding for the usual human dilemmas of middling writers: war and peace, love and sex, career ambition, inability to control complex situations, and so on. These dilemmas in their turn provide filling in between depictions of battles and little historical cameo moments for the fans that make up most of the appeal to most readers of end of history era alternate history.

In many ways, this space of fiction maps onto the general space of politics that the philosophers of the End of History provided, which is also sometimes considered the era of “there is no alternative.” What we had, and the mental armature that comes with it, is what we have, and it’s not going to change. History, in this vision, becomes a set of dusty museum pieces to be mulled over. If anything, the difference between the alternate history space and what someone like Francis Fukuyama thought about things is that Fukuyama would have understood that in the past, people really did think differently, not just in their opinions about issues but in their patterns and concepts, in a way that writers at the time (or now) only seem to fitfully understand. Different thinking means a modern person can rook an ancient person at strategy if they get zapped back to the last, in these novels, because ancient people are (supposedly) mentally inflexible… that’s the level of sophistication at which they generally work.

Allow me to fill in the space we’ve created for End of History alternate history fiction a little before we turn to what changed as the twenty-first century wore on. I see there as being basically two engines for the alternate history mobile as it chugs along, picking up readers on its tour for what it thinks of as the garden of forking paths but what is actually more like a carousel or Disney theme ride. The first is Harry Turtledove, of course. Like a certain kind of car, you know what you’re getting when you pick up a Turtledove novel. You get high concept what-ifs that can usually be described in one sentence. You usually get some war- war is important to a lot of alternate history fiction from this era, which had few fun conventional wars for nerds to gawp at. You’ll get a few awkward heterosexual sex scenes each book. You’ll get disasters but little really changes save for some borders and who is alive and who is dead.

The second engine of End of History alternate history consists of online alternate history fans who wrote their own series. These were often better-written and more historically rigorous than published alternate history fiction. They often took the form of hybrid works combining omniscient history-book style analysis with narration from fictional viewpoint characters. They often pushed the envelope, too, with the historical concepts more than your Turtledove types did. In the end, though, a lot of the successful series in places like the Usenet group soc.history.what-if can be read as parables of how badly wrong things could have gone had anyone messed with the history that resulted in the triumph of liberal democracy circa 2000. An Australian I corresponded with wrote “Decades of Darkness,” which situation is brought on by New England seceding from the union during the War of 1812 and allowing the rest of America to become (what else) a slave superstate. The serial often considered the crown of the genre, “For All Time,” starts with FDR dying, relative progressive Vice President Henry Wallace becoming President, and a series of disasters occurring which culminates in nuclear war, mass cannibalism, and Jim Jones becoming US President thirty years later.

There’s some outliers that deserve talking about, too, who did things a little differently but still belong firmly in the literary space we’re talking about. One is familiar from a lot of our adolescent readings: Orson Scott Card. Card was big stuff in the nineties, coming off of the success of Ender’s Game. In 1987, he began the Alvin Maker series, a series of fantasy novels set in a version of early nineteenth century America where the various magical traditions of its inhabitants work. The first two books in the series are actually pretty good, and it’s a compelling concept. The reason I bring the series up here is that both point to a historical apotheosis outside of the End of History concept while remaining well inside their idea space. The answer to the riddle of how that can be is Mormonism. Any non-Mormon reader of the Alvin Maker series knows the sinking feeling of reading the series, getting into the latter books, and before the action gets stupid as Card becomes a worse writer, it turns into obvious Mormon propaganda. Alvin Maker is going to fix everything, the broken promise of America, by incorporating all of the magic traditions of the continent’s inhabitants, white, black, and red, into his anti-entropy super-magic and start up a golden city in the west. This sort of redemptive narrative is also seen in his novel “Pastwatch,” where time travelers go back to 1492 and make the indigenous peoples and Christopher Columbus, here depicted as a decent put-upon striver following impossible orders, become friends. Everyone can get along if they just hear the good news.

And then there’s S.M. Stirling, with his aforementioned oscillation between slave empires and… not-slave empires. Among other things, Stirling was a participant in online scifi discussion groups for a long time, and was notorious for getting in flame wars that led to him being banned from forum after forum (he seems to have calmed down some in the tens- he has a Twitter but doesn’t use it that much). This is part of how we know that genocide and slavery aren’t just fantasies for him. He would make big, Heinlein-esque declarations about how genocide solved many problems, that Muslims as a whole were an enemy of western civilization, etc etc. From what I know of his biography, he’s a classic child of late empires, with an Anglo-Canadian dad (no one loved the British empire like nerdy men from the white settler dominions) and a French mom. So it makes sense why the romance of settler empire — and you see it again and again in his work, not just with the slaver Draka — would appeal so strongly.

The reason I talk about Stirling here isn’t to own him for being a reactionary. For one thing, he would try to wriggle out of that by pointing to his liberal heroes and reactionary villains. It’s true that the Draka get into a Cold War with the United States where he frantically signals that the US are the good guys (spoilers: the Draka win because they’re tougher). It’s also true that his time-stranded Nantucketers go around the Bronze Age world freeing slaves. Stirling does seem to see these actors as heroes doing heroic things- but also allows that slavers, Nazis, and genocidaires can be heroes too, because heroism is ultimately defined by strength. Beyond the politics, I think, to put it bluntly, he gets off on slavery. His slave empires, the Draka and others, have a lot of sex Stirling would probably think of as kinky, but which any millennial would instantly ID as fairly standard misogynistic slavery-based nonconsensual S and M between men and women or between women and women (among the Draka, for instance, Draka men routinely rape slave women but Draka women, liberated in most instances, never rape slave men- Stirling knows where to draw the line, and it’s where he stops being horny).

At times, Stirling has his good liberal heroes denounce the lack of consent as a concept amongst the Draka or the bad guys in the Change universe or wherever. One is even tempted to believe that Stirling believes it, with his brain if not his libido. But it’s also clear that he loves the Draka, and loves his settler badasses more generally. They’re always tough, always smart, always sexy. Most of them see the problems with their system but philosophize them away, often with reference to their responsibility to keep things from getting worse- we are supposed to believe this constitutes depth of character. The process of settlement gives life meaning, provides opportunities for mastery, allows the good life. The liberals in Stirling stories often lament the pointlessness of their societies or else find a settlement-substitute, like space exploration. Stirling’s good settlers and slavers are usually from classy old money, and the bad ones are tacky new money, bureaucrats, gangsters, etc. The slaves have mostly resigned themselves to their lot and are often quite frisky, sexually speaking. You can almost appreciate the lengths to which Stirling goes to make every instance of upsetting a slave or settler applecart into a hideous pointless atrocity, really upping the pathos… if you’ve a strong stomach. Here, we see the prevalent patterns of thought in the End of History era — rebellion as tragedy — coincide with good old fashioned sexual pathology. This is a good time to google image search “S.M. Stirling” if you want a funny little stinger to the whole thing.

As it happens, I could stomach Stirling as a teen. I didn’t read the Draka books, they weren’t at Borders and what I knew of them from the forums made me leery, but I loved (and often pestered my friends about) the Change series, the ones with Nantucket in the Bronze Age. And as it happens, I can stomach him as an adult, too, though that’s partially because of my training as a scholar of the right and of genre fiction. Stirling’s a pretty decent action writer, and writing good battles and fights isn’t as easy as it sounds. The sheer verve and gusto of his world-building concepts and the way he wears his weirdness on his sleeve — even as he thinks he’s completely normal! — can’t help but stir my admiration. The first Draka novel in particular is pretty good, because it gets into a genuinely alien headspace — Stirling, I think, did a lot of weird reading in old race theory and reactionary thought before starting — and has good battle action and, critically, is only about two hundred pages. What poisons Stirling’s work isn’t being a reactionary crackpot. It’s bloat and sentimentality. As he got older and more established as a writer, he asked fewer interesting questions, wrote much longer books with a lot of filler, repeated himself, and, perhaps in response to the Internet interlocutors we know he paid attention to, softened a lot of edges of his heroes and made his bad guys more capital-E evil, both in hammy Disney-style ways (also making the bad guys even rape-ier). It doesn’t work. His shit is still weird and creepy but hasn’t been that way in a fun way for a while. But it sold, especially during the End of History period.

So! We have a reasonably fleshed out ecosystem of alternate history writing circa the End of History. What happens when history comes back, around our admittedly somewhat arbitrary milepost of 2008?

Let’s once again get the relatively obvious Internet-style “ideology critique” out of the way first. There is, indeed, a good amount of back-and-forth pertaining to capital-H History, in the mode of ideological conflict, in contemporary alternate history fiction. Things like slavery and genocide are treated not as just unfortunate aspects of the human condition but as the product of power relationships that deserve to be critiqued and overturned. Many writers put a great deal of attention into matters of representation, what sort of characters they have doing what. I actually don’t see that as a complete break from earlier eras — if nothing else, your old scifi heads, including some of the alternate history guys I’ve spoken about, knew putting objectionable ideas and actions on characters from put-upon groups helped them get over — but there’s a different sort of focus on it now. Sometimes it drives more serious attention to character, sometimes it’s tokenism, but I will say the character-representation question does seem to eclipse other ways that writers could use to interrogate difficult subjects and create interesting perspectives.

Let’s see if we can’t elevate ourselves beyond the culture war set pieces by going through them, like striking through a target. In the ideological conflicts that have roiled the speculative fiction scene in the last ten years or so, the reactionary side accuses the liberal side of neglecting entertainment in favor of political sermonizing, mostly about identity. This is patently false. Liberal scifi favorites like N.K. Jemisin, Ann Leckie, Yoon Ha Lee and the rest pack their stories with all the space battles and twisty betrayals you want. Reactionary and liberal scifi both seem to borrow from the same basic sources these days: video games, anime, role playing games, comic books, and major crossover hits like Harry Potter and Game of Thrones. It’s clear that what the “puppies” and other reactionary fans object to is their inability to project onto heroes who might be women, or queer, or people of color.

What does it mean when the argument over the nature of speculative fiction — which is meant to be an exploration of human and even beyond human possibilities — so often becomes a question of projection, that is to say, one of the more common modes that viewers use to criticize pornography? They don’t like this actor because they can’t project onto him, they don’t like this actress because of X, Y, or Z flaw that they could only care about in their peculiar viewing situation – they can’t imagine themselves the captain of this particular spaceship, engaging in this particular mission, it’s all the same shit.

Let’s use the sort of internet pronunciamento about the current age I usually don’t like, just as a pry bar to help us understand: the idea of the death of context. It’s not really dead, plenty of people get context. But it’s true enough in the case of the projection complainers, either in scifi/fantasy or in pornography. Why should they need any context for their decisions when they’re just looking to jerk off? To whom must they explain themselves? Ironically, as the eye of the surveillance machine of which the Internet makes up a large part steadies it’s gaze on us, many of us imagine ourselves alone to satisfy our consumer preferences, isolated from all other considerations. It seems clear that more and more of us are incapable of understanding choice in any other way.

I see this mode of consciousness as a product of the conjuncture between the maturation of consumer economics in the late twentieth century and the concomitant collapse of shared public narratives about how life, politics, society and much else functions as the Cold War wound down and finally ended. In short, the discursive mode that seeded much of the ideological turmoil in speculative fiction — and, I’d argue, that is currently eating criticism alive — gathered much of its strands together in the End of History era.

So- it’s all a continuity, right?! Joined together by superficial readings, mediocrity, context collapse, etc? Well, a graph is a continuity- starts one place, continues on into another. At what point in the graph is the change it depicts significant enough to become a rupture? That’s the kind of question that bothers a certain kind of historian. It sort of bothers me but I won’t dwell on it. Spend enough time thinking seriously about history and you’ll get used to seeing continuity and rupture together, creating continuities and ruptures out of their opposite numbers.

But here’s a rupture for you: intellectual and cultural historians identify the end of the twentieth century with the collapse of consensus narratives that dominated public life, in America and many other societies, in the early and mid twentieth centuries. A lot of these histories are pretty good but they tend to be two panel comics: first, Americans by and large agree on a broad consensus around what you could call moderate nationalism, anticommunist liberal democracy, gradual progress in terms of equality of opportunity, and so on. Panel two, people no believe, or if they do they mean completely different things when they talk about these concepts. But it doesn’t make sense it would happen just like that.

Rupture and continuity: science fiction and fantasy in the twentieth century has been a site for the exploration of unusual and uncommon ideas (including being a place where seeds of extremist ideologies understood in midcentury as unamerican, mostly on the far right, could estivate, waiting for a better climate). But there’s continuity- in many respects, science fiction held to the idea of a common core of truth, generally identified with science, it’s progress, and the social progress that is meant, mutatis mutandis, to go with it, longer than it was necessarily fashionable in more “literary” publishing circles. Moreover, it seems pretty likely that Francis Fukuyama, when he wrote The End of History, thought he was ushering in a new consensus, at least among elites, not heralding an age of consensus collapse.

Let’s get back to alternate history: with the inevitable exception of Terry Bisson (an old SDS and antifascist hand, it’s worth noting), the major alternate history producers of the End of History era, even if they didn’t buy or even know about Fukuyama’s proclamation, all, in their way, pay tribute to the last thing that could pose as a consensus picture of history — the progress and triumph of liberal democracy, capitalism, and western science and technology — even as they honor it in the breach by creating alternate history scenarios where everything goes the other way. Even Fukuyama thought the End of History would prove tiresome, especially for people who dig war, like most scifi nerds do. The consensus picture of history is the negative against which the alternate history scenarios of the End of History period could be read. I don’t think it’s a total coincidence that this was also the height of the subgenre’s visibility.

A rupture with a continuity: many of the big names of alternate history fiction from the End of History era are still plugging away in the genre. Eric Flint turns out stories of his West Virginia mining town democratizing Europe after getting zapped back to the Thirty Years War. S.M. Stirling has a series about Teddy Roosevelt winning the presidency in 1912 and starting the CIA, but cooler, early. Harry Turtledove, who really has seemed to have given up, wrote a story about Stalin being raised in the US but still doing all of his Stalin stuff as US President despite his life being completely different from babyhood. Where do these guys figure in the ideological conflict that has occurred in scifi/fantasy in the last ten years? You’d figure they’d be involved, especially with Stirling’s documented love of online flame wars.

The answer: almost nowhere. Stirling used to try to start fights with left-leaning writers early in the period but seems to have settled down of late. Occasionally, given what the Draka series looks like, left-leaning writers use his work as an example of what reactionary scifi looks like, but he’s a third-stringer there next to gaudy assholes like Ted “Vox Day” Beale. Some commenters use Eric Flint’s allegiance to the publisher Baen, which publishes a lot of the major reactionary military scifi writers, as proof that said publisher is beyond ideology, given Flint’s background as a Trotskyite organizer. Turtledove’s nowhere to be found. I tried to find commentary among the Puppygate types on alternate history. It doesn’t seem to be something they’ve thought a lot about. And if they’re not thinking about it, their opposite numbers, speculative fiction liberals, aren’t thinking about it much either, even as some produce alternate history fiction themselves. The alternate history greats of the End of History era are now like so many of our legacy cultural institutions, seemingly going mostly on inertia.

What does alternate history mean in a situation where there isn’t really a consensus idea of what happened in actual history? You could argue that many of our fellow citizens are, essentially, living in alternate history fiction scenarios already. Here, I draw a distinction between people living with inaccurate ideas of the past in their head — that’s everyone — and people collaboratively recreating history according to standards that the participants may think are those of actual history, but are actually many of the same standards that go into creating genre fiction: entertainment value, emotional satisfaction, potential for viral spread. Think QAnon, but that’s only an extreme example.

We have also seen a collapse of genres along with context and consensus history. Alternate history becomes one trope among many, and easily mixed with all kinds of others between and across genres. You can index this to the rising prevalence of alternate history fiction that throws fealty to science out altogether. There was always magic or what amounted to magical technology in alternate history fiction. Most of the time, before our current era, the magic was restricted to a single moment- something gets shifted in time, a single advanced technology becomes available, and we follow the historical changes. Stories where magic and ultra-technology exist throughout the story, as part of the setting, are much more prevalent in alternate history fiction written now.

Alternate history writers of the late twentieth century were among the first to seize upon the possibilities of “alternate dimensions” and the many-worlds interpretation, as shown by subgenre progenitor’s H. Piper Beam’s “Paratime Patrol” series, the inevitable alternate-dimension-cop series by the inevitable Harry Turtledove, and so on. But the many worlds came into their own not with the schematic stories of the late twentieth century where, with few exceptions, there was a stable reference point — America, circa whenever the piece was being written — but with contemporary scifi- and not high end writers either. Those of you who think I’m a genre snob, hear me now: comic book fans and fan fiction people get many-worlds — they “grok” it, to use a term from an old scifi lion — in ways that the old scifi masters generally did not. You have to hand it to them. They navigate a world of few stable reference points. Sure, there’s canon… but who cares? Your real fan fiction head keeps a great many realities in their minds at once, lord love them. Horniness, narcissism, obsessive completism, and pedantry have driven your true fan into a mental space that had precursors before the 2008 breach but really only came into its own after.

Alternate history scenarios, then, become so many branches of the noosphere, the realm of ideas, nothing separating them from Tolkien’s Middle Earth or any other product of the human imagination- from the world of QAnon, for that matter. I suppose if there’s a thesis here, it’s to say that the late twentieth century — arguably the whole second half — was a time of unusually strong divides in the noosphere, that people believed in, and that many of those divisions have since collapsed, leaving us in the situation we’re in today. After all, who’s to say somewhere in the many worlds of ill-understood quantum physics there isn’t a Middle Earth, or a world where JFK Jr faked his death to battle the deep state, or the scariest world of all, wherever the fuck The Brave Little Toaster happens? Well, physicists are to say, but who cares about what a Steven Hawking might have to say next to what Rick Sanchez offers our imaginations?

In the collapse of consensuses from the definition of genre to the understanding of history, we have a freedom that has naturally led to an effervescence in alternate history fiction, and in speculative fiction — in art — more generally, right? Of course we did- just like how the Internet democratized information and made people much smarter and less susceptible to misinformation. To use an expression from the End of History period and my youth: NOTTTTT! Contemporary alternate history fiction is mostly pretty lousy, much like the alternate history fiction of the late twentieth century. Most of it abandons efforts at being historically rigorous, which would be fine, a good thing even, if they did anything especially creative with it, which they usually don’t. You wind up with a lot of just-so stories and tedium, at least in part, I think, due to the shadow of YA fiction and other influences that don’t especially encourage critical thought about what a given writer is really doing. Contemporary alternate history fiction tends to be shorter than the honking long series of yore, which is nice, I guess.

Here’s a suggestion: maybe instead of adopting a single story, or just giving the nod to any story that comes down the pike, we apply our critical capacity. We acknowledge that there’s a reality that we live in, that not everything is equally true or untrue, but also that we have imaginations, capable of seeing things that aren’t there, for a reason, to imagine possibilities and impossibilities. Maybe we can try out some old ideas and some new ones as something other than set-dressing. The first that comes to mind is the dialectic, the creation of new ideas through the opposition of existing ones, like that between our concrete realities and our limitless imaginations. Maybe games are better with rules, because everyone can play- and everyone can make new ones, everyone can make house rules with their friends. Maybe we could try communicating, but first we’d have to come up with something to say. When we do, then we can walk onto the path of the many worlds as though we belong there.